Glenn Gordon Caron (pages 123-129)

The Twentieth Century-Fox movie lot is one of the few left in Los Angeles that conjures up the glory days of Hollywood filmmaking. Maybe that's because when you get past the security guard, you're automatically on a movie set. Gene Kelly turned the exteriors of many of Fox's offices into a replica of turn-of-the-century New York for Hello Dolly! In 1967, and Fox made the decision to leave it that way-a movie lover's dream.

Fox is also the home of Glenn Gordon Caron, the young creator and executive producer of the successful and stylish series Moonlighting.

Fox is also the home of Glenn Gordon Caron, the young creator and executive producer of the successful and stylish series Moonlighting.

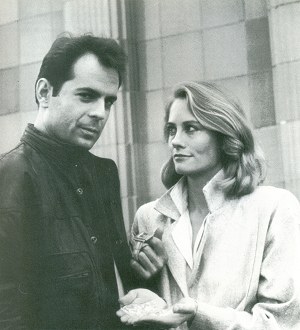

Moonlighting, the detective series starring Cybill Shepherd and Bruce Willis, is about the Blue Moon Detective Agency, the only asset model Maddie Hayes (Shepherd) had left when her business manager absconded with her career earnings. She runs the agency with wisecracking, good time private eye David Addison (Willis) and their loyal, if perpetually bewildered, office manager, Ms. Dipesto, played by Allyce Beasley.

Moonlighting takes episodic-television traditions and throws them out the window. The show's scripts are filled with humor, sexual innuendo, and innovation: a show done totally in black-and-white, for example; a big-budget parody of The Taming of the Shrew; a dream ballet sequence, choreographed by Stanley Donen; all punctuated by knowing asides to the camera. Sometimes these experiments fall flat, but Moonlighting takes the chance.

It's appropriate that Caron should have his offices at Fox, for he is, above all, a movie junkie. While he is a fan of television, it's the movies he keeps going back to for inspiration. As a student at the State University of New York at Geneseo, he booked movies for the college film series. "We would steal the sixteen-millimeter print afterward, take it, and run it on a-it wasn't even a moviola, it was just a single scope with two rewinds. We'd look at how the scenes were cut and then scream about them to each other-why this worked, why that didn't work. We would have knock-down, drag-out fights about the way Straw Dogs was cut. It's very hard to work up that kind of head of steam about television."

Graduating from college, Caron knocked around for a while in New York and Chicago, studying improv in Chicago with Del Close and Second City. Eventually, he moved to Los Angeles, never intending to go into television. "I started writing because I couldn't afford to make a film," Caron said.

"Somebody said to me, 'Why don't you write a film? Costs about three bucks, and if you get a good job and they have a Xerox machine, it costs you even less.'

"I started to do that, and at one point, my work started to get a little bit of attention, and an agent-he's my agent now-Elliott Webb, signed me. He was with ICM at the time, which is one of the big talent agencies in town.

"I don't know if that is standard; I know it certainly was the case with me. I think the way they sign you is they kind of look at you and go, 'Movies, movies, movies…'

"You go, 'Great!' and you sign.

"Once they've got you, they go, 'Television…'

"You go, 'Huh?'

"They go, 'Television, it's a wonderful place to start your career, blah-blah-blah…'

"I kind of scratched my head and said, 'But I don't want to work in television. I don't watch television.'

"They said, 'Why don't you go home and watch some television?' So I went home, and I turned on the TV, and there was a show premiering called Taxi, which I just thought was terrific. I picked up the phone the next day, and I called Elliott up, and I said, 'I'd like to do Taxi.'

"That's really how I started in it. Very strange."

Taxi, which ran on ABC for four seasons and on NBC for a fifth, was one of those shows-such as The Mary Tyler Moore Show and Cheers-that found real comedy in human relationships, without eschewing the one-liners and sight gags of more traditional sitcoms. Caron compared it to the experience of writing Moonlighting: "We don't sit down and say, 'Let's write some comedy.' This is going to sound kind of artsy-fartsy and pretentious, but what we try to do is sit down and say, 'What's the truth?'

"I bristle a bit at 'This is a comedy, this is a drama.' What we try to do is get to the truth, whatever that is, and if the people involved are inherently funny, then certainly some humor will emerge. But we don't sit down in a conscious way and say, 'We're comedy, we're drama.'"

Caron has worked in both, piling up an impressive list of credits for a guy who's only in his early thirties. He was the story editor of Good Time Harry, a short-lived series about a sportswriter that had a cult following among critics and the few viewers who could find it buried in the NBC schedule; a writer and producer of Remington Steele; and the creator of two pilots produced by his own company, Picturemaker Productions. Both pilots, made for ABC, failed to become series, but the network was impressed by Caron's work.

"Lew Erlicht, who was running the network at that time, took me out to lunch. He said, 'Look, what you do is weird. I'm okay with that, and I want to put you on television, but you've got to help me. You've got to write in a conventional genre. Something that I could schedule.'

"I said, 'Like what?'

"He said, 'Let's do a detective show,' and I just, I mean, my eyes rolled to the top of my head. I think I said something to the effect of, 'That's what America needs, another detective show.'

"He said, 'Well, just think about it, and think about a star.' He rattled off a bunch of star names-you know, some of the women who had appeared in Charlie's Angles and some other things. I kind of left the lunch depressed-because I've been very lucky. I've almost never done anything my heart wasn't in.

"But I thought about it a while, and I went back to him. I said, 'Let's get together. Let's have a meeting. I have an idea of what I want to do.' So we all got together, and it was a twenty-second meeting. I said, 'I'll do your damn detective show'-I mean, I think that was my tone-'but what I want to do is a romance.'

"Lew said, 'Fine. Go ahead and do it.' He may have said, 'What's the premise?' And I think I might have told him about a model who's lost her fortune and she's left with all these things and one of them's a detective agency and there's this guy and hooda-hooda-hooda. But I mean, maybe forty-five seconds tops…

"So I went off. In fact, I remember leaving his office, walking down the hall, and suddenly the door opened, he said, 'What's it called?'

"And I went, "Ahhhh--Moonlighting!' I don't know where that came from."

|

|

Combining high elegance with outlandish humor and double entendres, Moonlighting is a comedy romance that masquerades as a detective drama. The series brought TV stardom to Bruce Willis and revived the career of seventies movie star Cybill Shepherd. Moonlighting's popularity has allowed it to experiment with a variety of wild format ideas-from a parody of Shakespeare's Taming of the Shrew to a sequence in which Shepherd and Willis appeared as clay animation figures. |

The result was a totally unexpected delight. "A lot of what Moonlighting is, is a function of my boredom with the form," Caron said. "Me trying to stay awake. One thing that makes it different is that there's this sense that these people (David and Maddie, the leads) know they're on television. They watch television. They're bored with the form, too.

"The audience is also obviously TV savvy," Caron maintains. He believes that a show like Moonlighting might not have been able to pull off its tongue-in-cheek attitude about TV ten or fifteen years ago. "I'm not sure that the history of the relationship between the viewer and the television set was deep enough at that point to get away with that. But the idea isn't new. You ever watched the old Hope and Crosby pictures? Invariably, once a picture, they turn to the camera and say something like, 'Can you believe we're doing this?' It's certainly not a new idea. I think even Shakespeare fooled around with it--I did a series with him, by the way. He's very overrated…"

He does find it hard to pin down all the various popular-culture influences on the series.

"There are phonograph records that influenced Moonlighting, music I was listening to at the time. There are movies that I've seen that seem to have nothing to do with Moonlighting, and yet, they are important to me, and so they'll creep in at some point…

"One thing we did do deliberately--Bob Butler, who was the director of the pilot (and also the director of the pilot for Hill Street Blues), suggested that we sit down and watch His Girl Friday (Howard Hawks's reworking of the newspaper comedy classic The Front Page with Rosalind Russell and Cary Grant), because I kept talking about how the dialogue has to go a hundred miles an hour. Bob Butler said, 'Why can't they talk at the same time?' So we watched His Girl Friday; in fact we showed it to Cybill and Bruce to get a sense of what the limits are, because Hawks did it better than anybody. That's a direct influence.

"But there are other things knocking around in there. I'm a huge Frank Capra fan. And, by extension, a huge Joe Walker fan; he was the cinematographer on the Capra pictures. Gerry Finnerman who's our cinematographer, lights with hard light, which tends not to be the rule today in television. Takes a little longer, but I'm a big fan of turning off the lights and playing a scene in the dark. I'm a big believer that people say things at night that they wouldn't say during the day. They say things when it rains that they wouldn't say when it's sunny. A lot of that comes from watching Capra pictures.

"Body Heat sort of got me reinterested in the whole James M. Cain sort of geometry on a mystery--Double Indemnity and all that. Particularly during the first five episodes that we did, early into the first season, we played with that geometry quite a bit."

Caron enjoys working in television for many reasons:

"You get an idea on Monday, you write it down on Tuesday, you shoot it on a Wednesday, and it's on television the following week. Bruce Willis always kids-he calls it Film College. I get a texture in my head, or a color, or someone else will-an idea-and we have the means with which to try it, to reach for something. And some of these things are nuts.

"They defy any kind of rational…you know, I had this idea in my head, storytelling with dance, which hadn't been done in a long time. I said, 'Wouldn't it be wonderful to just do a seven-, eight-minute thing?' So you call Stanley Donen, thinking he'll hang up on you, because he's the master, and he says yes! How often does that happen?

"I remember two years ago, when we had the idea of doing the black-and-white show. I was certain that I'd go to ABC, say I want to do this show in black-and-white, and the roof would fall in. They weren't concerned.

"That's why I work in television, because the palette is certainly as broad as film, and the freedom is there for me, and (knock wood) the audience, for the moment, is there.

"That's the other thing-it's the biggest house in the world. You're playing the biggest theater there is, and when you do it well, they sure tell you. When you don't, they tell you, too. The feedback's pretty immediate. It isn't like a motion picture, where you make it, and for six months everybody sort of sits and ruminates about it, and then you put it in theaters. It's a different experience. That's why I work in television."

The movie addict in Caron is obsessed with the look of Moonlighting, one of the series' most distinguishing features, "I had always seen the show as a romance," he reminded. "Sort of harkening back to what notion of romance in film was-going back to those Capra pictures, in which Barbara Stanwyck would come in and sort of tell the truth to Gary Cooper. Those scenes always seemed to play in the dark, so we were determined, if and when we were allowed to do the series, to get someone who was comfortable with that." They hired Gerald Finnerman, who was trained in the old school of Hollywood camerawork.

All of this, of course, is expensive, and Moonlighting has a reputation for being one of the most expensive hour-long shows on TV. Caron doesn't bristle at the suggestion-but he says immediately and unequivocally, "Want me to do my speech?

"The thinking in television which makes no damn sense to me, is that a half hour of television costs X, and an hour of television costs Y, no matter what that television is, it strikes me as an insane hypothesis. The parallel is, you're hungry, whether you go to McDonald's or whether you go to '21,' it should cost the same; they both fill your stomach. It's nonsense.

"I once sat down and figured it out. I believe we are the cheapest show per ratings point, certainly on ABC, and when you really get down to it, that's what ABC is selling. There are other shows that are in the same ballpark, as us. ABC is getting their money's worth. If they're not, they have the wherewithal to do something about it. I don't apologize for what the show costs at all.

"If you want quality, I think you have to expect to pay for it, and I think the viewers have said in a very clear way that they want quality. Not an unreasonable thing to ask, because you have to remember that when the viewer sits down and turns the channel selector, he doesn't differentiate between ABC, NBC, CBS, and HBO. Which means that my show which costs a million something, or Michael Mann's or Steven Bochco's is more than likely competing against a movie made by George Lucas that coast thirty-something million. It's still free to the consumer. Sure, he writes a check at the end of each month to HBO, but when he sits down and makes the choice, nobody's asking him for his money….

"So from where I sit, a show like Moonlighting is cost effective. Everybody's making a profit. The question is how big a profit. The thinking that needs to change isn't here. I'm not sure it's in Hollywood. I think it's in New York, on Wall Street."

Another facet of Moonlighting that has made the show somewhat controversial is its out-and-out, blatant sexiness. Yet, Caron claims not to have had the problems with network censors mentioned by other producers and writers. "We have a terrific relationship," he claimed.

"Beginning with the pilot, we've had an agreement with them that if there's something they're uneasy with or uncomfortable with, I film it and show it to them on film, with the understanding that if they continue to have a problem with it, we can offer them some remedy. They very rarely ask us to do that.

"My argument to them has always been, see it in context. On a page, you can't into account all those other elements that are what a film is. They've always been kind of great about that.

"I think they one thing that upsets them a little bit is that, unfortunately, they get to see it incredibly late, because we've fallen into a pattern of delivering our shows very late.

"It's their air, you know? It's their movie theater. Ultimately, I'm not responsible. I mean, I'm responsible for the quality and the content of Moonlighting. I'm responsible to the viewers. But they (the network) are responsible at some point to the government and all that kind of thing, so it's very hard to begrudge them that voice."

Why are writers like Caron willing to take on so many responsibilities as a producer? "Producing in television is a natural outgrowth of wanting to control the work," he said, "since the ideas tend to begin in the writer's mind and also because the writing is probably the most elusive commodity in the whole chain of events that yields a television show. So from a business point of view, there's a natural inclination to say, 'Let's make the woman or man who's doing the writing in charge of the whole darn thing.'"

Television has won over the film student:

"It strikes up this kinship, you know? I see it on our show: the relationship that the audience has with the show. It becomes personal in a way that no other medium can because of its immediacy-that's what television does best.

"I don't think in history any part of the entertainment business has taken on the challenge that TV does, which is to create sixty-six new hours of entertainment a week. Hollywood in its heyday didn't do that. Measured against that yardstick, we're doing okay.

"What's wrong with TV? We're asked to make it too fast. We're asked to make it too inexpensively. There's a tremendous temptation to homogenize everything-an overabundance of concern about offending. I think part of the dramatic experience has to do with unsettling you a little. I mean, even as children--Lassie Come Home--if you were alive and the picture worked for you, you cried at the end. That was what it was about.

"Steve Bochco says-I'm going to misquote him, but the thrust of what he said was that all art begins with a point of view. And the temptation in television is to deny point of view. We want to be fair to everybody. No good drama, no good art comes out of that."

DavidandMaddie.com Home Page

E-Mail: webmaster@DavidandMaddie.com

This is not meant to violate or infringe on any copyrights.

It is just a labor of love and is for entertainment purposes only.

© 2002-2004. All rights reserved. CYber SYtes, Inc.